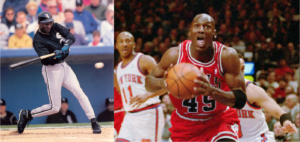

A sports legend leaves the world he’s most familiar with to begin a career in one that he’s not as familiar with. After spending many years away from the diamond, and forging a legendary career, he decides to revisit his baseball ambitions. He realizes that being a one-sport superstar is one thing. Trying to become a two sport star is very, very different. After one hundred twenty-seven games and four hundred and thirty-six at-bats he boasts an offensive line of:

.202 3HR 51 RBI 30SB and 114 Ks

In 1995, baseball was still on strike (before shifting to an owner-run lockout) so Michael Jeffrey Jordan donned the familiar red and black Chicago Bulls uniform (with the very unfamiliar number forty-five) and dropped 19 points in 43 minutes against the Indiana Pacers. Nine days later he regained his championship form, dropping fifty-five points against the rival New York Knicks. What lesson came from his foray into baseball? It’s not as easy as it looks.

Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders were rare athletes who could not only play two professional sports but also excel.

The 1985 Heisman Trophy winner, Bo was the star of the Nike “Bo Knows” commercials. These ubiquitous spots showed off his prowess in a multitude of sports as well as on stage with the legendary Bo Diddley. Jackson made all-star teams in both baseball and on the gridiron. No one will ever forget Jackson’s heroics in the 1989 All-Star game. Nor can we erase the image of Jackson climbing the centerfield wall to make an acrobatic catch for the Royals. Similarly Brian Bosworth is still licking his physical wounds and damaged pride when Jackson flattened him at the Kingdome.

Sanders played all-star caliber baseball and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall Of Fame. Never a very good tackler, teams changed strategies because he was like a centerfielder in the secondary picking off pass after pass after pass as he high-stepped to the endzone. “Neon” Deion was the classic sixty minute-man lining up on offense, defense and special teams. Sanders remains the only man to play in a World Series (1992 with Atlanta) and a Super Bowl (winning XXIX with San Francisco and XXX with Dallas).

Danny Ainge (basketball and baseball), D.J. Dozier (football and baseball) and Brian Jordan (football and baseball) are among many who have suited up for teams in two professional sports. Jim Thorpe remains the gold standard of the multi-sport stars as he played for the New York Giants (baseball), Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves in a six-year career spanning from 1913 to 1919. Over eight years he played for five teams during the infancy of professional football. And, of course, he received the gold medal at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics in track and field. Those medals were later revoked when it was revealed that he was a professional baseball player. That’s a far cry from today’s Olympics where all athletes are a part of a “dream” team.

Had he began playing professionally at a young age, Thorpe easily could have been the best football player in history. By choosing baseball, Jackson, having been drafted by the cellar dwelling Tampa Bay Buccaneers, derailed what could have been the most prolific football career ever. Sanders is already listed as one of the best defensive backs of all time. But can you imagine how much better he would have been if he didn’t play baseball? In an age where athletes are forced to specialize in one-sport, why not applaud Tim Tebow’s attempt to play baseball?

Tim Tebow’s NFL career boils down to one highlight. On the first play in overtime in the 2011 Wild Card game against the Pittsburgh Steelers, as quarterback for the Denver Broncos, Tebow connected with Demaryius Thomas on an eighty yard touchdown pass. The following season, he was traded to the Jets completing six passes on eight attempts for thirty-nine yards. Since then, he has not thrown a single pass in an NFL regular season game. This was after winning two national championships and the 2007 Heisman trophy while attending the University of Florida. There is no question that Tebow is a gifted athlete. He will always be considered one of the best quarterbacks in NCAA history. But as a pro, he’s a bust.

Letterman jackets used to feature several accoutrements of the multi-sport star. In order to showcase for colleges and professional scouts, gifted athletes are now forced to choose one sport. They will play in multiple leagues, in addition to their school teams. Tebow faced that same fate as well. He has not played in a competitive baseball game since his junior year of high school – over a decade ago. At the time he was all-state and hitting almost .500. Don’t forget that he played in the ultra-competitive Florida high school environment which has turned out hundreds of major league players (Gary Sheffield, Dwight Gooden, and Fred McGriff). Had he focused on baseball, he probably would be on a MLB team today.

At his recent showcase, Tebow did not blow away the scouts with his skills. He hit well, but not great. He was tentative in the field and his body type (6’3”, 255 pounds) is not really conducive for a baseball player. He does, however, share an agent with Yoenis Cespedes. Signing Tebow was met with hate and criticism on talk radio and social media. That signing, on the other hand, could result in some quid pro quo should Cespedes decide to opt out following the season. To be sure, Tebow is a controversial personality. He’s deeply religious and years before the “dab” he would celebrate touchdowns and victories by kneeling in personal prayer. This move became known as “Tebowing.” Put all of that into perspective as you also consider his intensity and will to win.

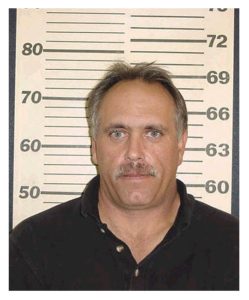

For over a decade baseball fans were delighted by the filthy uniform and intensity of Walter Wayne Backman. Wally suited up for five professional teams including nine very fiery years with the Mets. Hitting second and playing second base, he was a switch hitter but was used mostly from the left side of the plate behind Lenny Dykstra. He was a vital cog in the Mets post seasons runs of 1986 and 1988 as well as their near misses in 1984, 1985 and 1987. His intensity and body-first attitude translated into a career in coaching. He is among several 1980s Mets who wound up becoming a manager (Larry Bowa, Ron Gardenhire, Lee Mazzilli, Ray Knight) or coach (Tim Teufel, Dave Magadan, Roger McDowell, Jose Oquendo). His success as a teacher and motivator translated into a managerial job with the Arizona Diamondbacks.

He was fired four days after being hired.

Revelations and accusations about alleged spousal abuse (a hot button topic in today’s sports landscape), tax evasion, drinking and anger issues derailed what could have been a promising managerial career. Sent onto the scrapheap, the Mets brought him back into the fold at a time that several other 1986 teammates were being given jobs. Teufel, Mookie Wilson, Bob Ojeda, Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling were brought back to link today’s fans to the Mets most recent World Series success. Having Backman mentor their prospects in the instructional leagues all the way up to triple A was a slam dunk. His teams won and his players made contributions on the major league roster. Most of all, his name would come up frequently on talk radio whenever one of their managers would become embattled. He was a finalist in 2011 with Terry Collins as a replacement for Jerry Manuel.

Minor league managing is a very unique skill set. Wins and loss matter, but not as much as player development. Being a minor league manager is less a field general than it is being a teacher and advanced scout. The rotation is constantly thrown into a state of flux when the major league team needs a spot starter. The lineup is set by the front office. You want to spell a player? Nope, he needs to see action against a left handed sinker baller. You want to bat a certain player sixth because you like the lefty-right match up? Nope. The front office wants him hitting second so that he can get extra plate appearances. Backman understood his role. When Lucas Duda went down, Backman suggested that the Mets sign James Loney. How has that turned out? Few people understand how tough that role really is. Bobby Valentine, after being fired by the Texas Rangers was faced with two choices: manage in Japan or become the Mets’ AAA manager. He did both. And it turned into a very successful run with the Mets in the late 1990s.

Backman’s exit combined with the Tebow signing is very interesting in its timing. Backman says he resigned because he didn’t see any place for himself at the major league level (as a coach or manager). Does Tebow have a place in the majors? Probably not. He can hit well in batting practice, but how can he handle a major league curve ball in a game situation. Is he really going to leapfrog Brandon Nimmo or Michael Conforto on the depth chart? Will he get valuable at-bats in place of a player that could turn into the next Darryl Strawberry or Lenny Dykstra? What value does a twenty-nine year old rookie really bring?

What both Backman and Tebow bring is experience. Tebow has played on the largest stages as well as been cut and traded. Backman saw World Series success but also has been fired. Prior to being drafted, players in the minors have lived lives of privilege. Dating back to little league they were probably always the best on their team. They were coddled and prodded and encouraged. When they got to the minors they were now at the bottom of the totem pole and had to deal with no longer being the best. Backman and Tebow both can understand those feelings. The benefit they can bring to those young players can be as valuable as extra batting practice.

Tim Tebow was born on August 14, 1987. At the time the Mets were 65-51 having lost to the Chicago Cubs 6-1. They finished that season 90-72 and in second place to the Cardinals. That result would have occurred whether or not Tebow was born. In contrast, Backman, still platooning with Tim Teufel, was a huge contributor helping to keep the team in playoff contention. As of this writing the 2016 Mets are 77-68 and within a game of the San Francisco Giants for the top wild card spot. Currently on their (expanded) roster are twenty five players who spent some time with Backman as their manager. Two players, Loney and Rene Rivera were signed because of Backman’s recommendations. The point is that signing Tebow will not change their fortunes this year nor will they influence the fact that they are the reining National League champions. Backman, however, can take direct credit for both of those facts.

Let’s face it, only the top one of two percent of little league stars will make their middle school team. And only the top one or two percent of those middle school team stars will make their varsity or travel teams once reaching high school. Only the top one or two percent of the high school stars will get a college scholarship. Only the top one or two percent of those players will be drafted by an MLB franchise. Of those players only the top one or two percent will ever actually become a major leaguer. Even slimmer are the chances that player will be a hall of famer. The point is that Tebow will not take playing time from a truly good player. No one who is counted on to contribute to the Mets fortunes will sit in favor or Tebow. Even Rick Ankiel realized that his life as a pitcher needed to be reimagined as an outfielder. Still he helped the Cardinals make several postseasons and did make a contribution. As the Mets see Backman leave, and the influence and experience walk out the door with him, they welcome Tebow into the fold. Who better to teach the younger players about adversity, competition and what it takes to win than a man who has experienced both highs and lows?